The Shroud of Turin and the Sudarium of Oviedo

The Shroud of Turin, Jesus’ burial cloth, and the Sudarium of Oviedo, the napkin that covered his head after his death, are both mentioned in the Bible. Matthew 27:59 tells us that Joseph of Arimathea took Jesus’ body, wrapped it in a clean linen shroud, and laid it in the tomb. John 1–7 relates that after Mary Magdalene told the disciples Jesus’ body was missing, Peter and John rushed back to the tomb, where John “saw the linen cloths lying there,” and then Peter “saw the linen cloths lying, and the napkin, which had been on his head, not lying with the linen cloths but rolled up in a place by itself.”

The gospel narrative confirms the existence of both the shroud and the sudarium, and it is because of their existence that we can more fully understand what happened to Jesus before and after the Crucifixion.

Jesus Is Entombed

When Jesus died, a post-mortem flow of blood and pulmonary edema issued from Jesus’ mouth and nose. Someone took a napkin, or handkerchief, and held it to Jesus’ mouth and nose, pressing tightly to staunch the flow. Then that same cloth was wrapped partially around his head and pinned in place with thorns, which were readily available. As Jesus’ head had fallen onto his right shoulder, the cloth was pinned to his hair and beard on the right side of his face, wrapped around the left side of his face and head and pinned again to the hair at the right rear of his head.

Jesus remained on the cross until Joseph of Arimathea received permission from Pontius Pilate to remove his body. Joseph returned to Golgotha, the site of the Crucifixion, and took Jesus down from the cross. He was laid on his back. The blood from the wound in his side ran down his right side and “puddled” in the small of his back. The napkin, or sudarium, was re-pinned to go all the way around Jesus’ head now that it was no longer resting on his right shoulder.

Jesus was brought to the tomb. Ordinarily, a dead man’s body was washed for burial, but if the man had died a violent death, the body was not washed so it could be buried with its blood. The law even went to the extent that, where a violent death caused bleeding onto the ground, earth mingled with blood was dug up and buried with the body.

When Joseph and Nicodemus, another member of the Sanhedrin, returned to the tomb with the necessities for burial, it was about 5:30 p.m. or perhaps a little earlier. They spread the shroud on the shelf in the inner room of the tomb on which bodies were to be laid until the flesh decomposed and the bones could be re-interred. The sudarium was removed and placed in the inner chamber. Jesus was placed on the bottom fold of the shroud, which was then folded over the top of his head till it reached his feet at the open end.

Myrrh and aloes were used as aromatics and to anoint—not to clean—the body, since it could not be cleaned due to the violence of his death and the necessity to leave the blood with the body. Other cloths were used, which are lost or destroyed. One was the chin band, apparent on the shroud, and possibly bands to secure his arms against rigor mortis. The women who had obtained flowers laid them inside the shroud. Faint images of twenty-eight types of plants, including twenty-three flowers, three bushes, and two thorn vines, appear on the shroud. All of them grow in the area of Jerusalem, some of them grow nowhere else, and twenty-seven of them bloom during March and April.

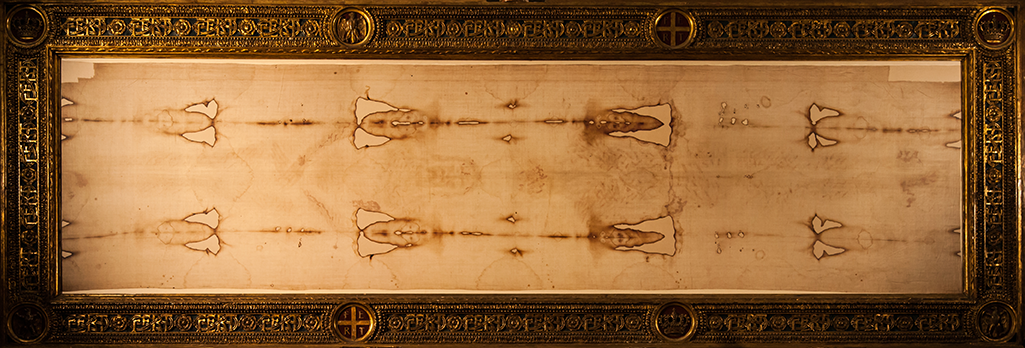

The Shroud of Turin

The Shroud of Turin is a herringbone-weaved cloth measuring 14’ 5” by 3’ 7” with the imprint of the front and back of Jesus. Blood stains shows the wounds he suffered: pierced wrist, gouge in his side, punctures on his scalp, and scores of wounds on his legs and torso. A detailed study of the shroud shows that two men, standing behind Jesus and on either side of him, beat him with the flagrum, a whip with multiple thongs tipped with bar-bell shaped pieces of lead. The shroud shows that Jesus received strokes sufficient to inflict more than 100 wounds, each about ” long.

Until 1898, when the shroud’s negative image was first observed, there was little effort to understand how the image of Jesus was imprinted on the cloth. Efforts to replicate the transfer of such an image to cloth have failed miserably. The detailed data on the shroud have been revealed due to the scientific advances of our technological age and could never have been detected in earlier times. It is as if the shroud had been encoded with data that could not be known until our own era and was intended to be a sign to an unbelieving, scientific age.

There are different theories as to how the image was made on the cloth of the Shroud. One theory makes the most sense. We know that, at a certain level, heat and light are interchangeable forms of energy. A flash of incredibly intense light for an incredibly short period of time theoretically could give off heat to scorch the cloth without destroying it. Therefore, the Shroud of Turin is best understood as a snapshot of the Resurrection. It was laid down 2,000 years ago as a special sign to our own technological age. As is always the case, the Lord not only does not compel belief, but rather he always leaves an escape hatch for unbelievers to justify and remain in their unbelief.

One final comment regarding the Shroud of Turin: Its most remarkable feature is the calmness and serenity of Jesus’ face, which does not at all accord with the tortures inflicted upon him. We are familiar with the fact that severe trauma or pain before death can cause such irremovable contortions of the facial features that such people have closed-casket funerals. Jesus’ face does not reflect such contortions. If he did go through his ordeal while preserving the serenity of his countenance, this would explain how the centurion could recognize that something extraordinary was occurring and conclude, “Truly, this was the Son of God.”

The Shroud of Turin, owned by the Pope, currently resides in the royal chapel of Saint John the Baptist in Turin, Italy. The last public showing of the shroud was in 2015. It is not scheduled for public viewing again until 2025.

The Sudarium of Oviedo

The Sudarium of Oviedo is a piece of cloth measuring 33” by 21.” It is of common fabric, unlike the fine, expensively woven herringbone-patterned shroud. The blood on the sudarium from the wounds at the base of the back of the neck is vital blood, blood from a living person, unlike blood from the nose and mouth. The wounds correspond with those on the shroud. The blood type is the same, AB.

The recent study of the sudarium showing seventy points of coincidence with the shroud renders it mathematically impossible for the shroud to have been a thirteenth- or fourteenth-century forgery. The sudarium had never been described in sufficient detail to have allowed such a forgery, if, indeed, there had been available a forger of sufficient technical proficiency. Even a cursory comparison of the quality and verisimilitude to the human form of the image on the shroud with artistic renderings of the human form done in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries shows that no such technically proficient artist existed.

The sudarium surfaced in Jerusalem at some time after Helena made her pilgrimage. When the Persians threatened Jerusalem in the seventh century, it was moved to Alexandria, Egypt, where it was venerated as the napkin containing Jesus’ blood. When the Persians threatened to conquer Egypt, it was sent to Toledo, Spain, for safekeeping. Its arrival and presence in Toledo in the seventh century is of historical record. As the Moslem conquest of Spain proceeded, the sudarium was sent north to relative safety. It was put into a chest and placed in the Holy Chamber of the Cathedral of San Salvador in Oviedo by King Alfonso II. The chest containing the sudarium and other relics was opened in the presence of King Alfonso VI in 1075. If the sudarium and the shroud were used on the same body, the shroud cannot be a thirteenth- or fourteenth-century forgery as some skeptics suggest.

The Sudarium of Oviedo currently resides in the Camara Santa (Holy Chapel) of the Cathedral of San Salvador in Oviedo, Spain. It is displayed to the public three times a year: on Good Friday, on September 14 (Feast of the Triumph of the Cross), and on September 21 (octave of the Feast of the Triumph of the Cross).